"We were only going to ask for two million," says Jon Koncak, still amazed.

This month, 35 years ago, Jon Koncak signed his second NBA contract.

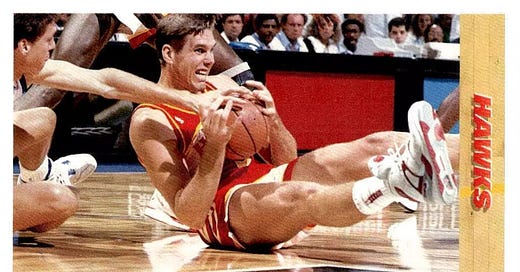

Koncak, a well-regarded 7-foot reserve center for the Atlanta Hawks, was a restricted free agent in 1989. Signed to an offer sheet by the Detroit Pistons after the 1989 NBA champions happened upon some unexpected cap space, the anguish of which was later expressed by Isiah Thomas in full view of the American president at the time, alongside assembled international media.

The Pistons, rolling in it, cranked Koncak’s offer sheet in a bid to disrupt the fortunes of the Atlanta Hawks, already dreary with cap-clopping dead weight. Instead, the Hawks matched the offer, Koncak remained a Hawk, and everyone lost their minds at the terms endowed upon the Southern Methodist University product. Most importantly, more ballplayers made more money. Even if one of them was Karl Malone.

Atlanta’s agreement? Six-years, $13.2 million. Reasonable marks for our modern reserve big man, JaVale McGee made $2.2 million last season, yet in 1989 Koncak’s contract was certification of impending cataclysm. The lessons learned from Gekko’s Eighties concluded with Hammertime, the 7-footers of the 1990s due to reap the millions, tens of millions, from the NBA’s peacocking decade.

The Atlanta Hawks weren’t ever the same after the club’s Game 7, semifinals loss to Boston in 1988. Hawk starting center Kevin Willis broke his foot in the offseason, to take his place Atlanta signed 33-year old Moses Malone at three-years and $4.67 million, to some ridicule. ATL dealt a first-round pick plus shooter Randy Wittman for 31-year old, 21-point scorer Reggie Theus, to much ridicule.

The collection won 52 games in 1988-89, two more than the year before, managing a top-four offense. Yet the anticipatory argument against Atlanta came correct by spring: Moses looked 2000-years old in the postseason, where Theus was an embarrassment and the Hawks lost to an even older Milwaukee club in the first round.

The Hawks even fought with Willis, suspending the big man when he refused to follow the club’s rehab orders (read: attend Atlanta Hawks games).

Meanwhile, Division-rival Detroit won its first NBA title in 1989, Division-rival Chicago battled the same Pistons to seven games in the 1989 Eastern finals, Boston was no pushover, the Division-rival Cavaliers won 57 games, Philly’s 26-year old Charles Barkley already eclipsed 29-year old Dominque Wilkins as the East’s more potent 20-something forward, and Division-rival Milwaukee was provably better than Atlanta. So, for 1989-90, the Hawks brought ‘em all back.

At some cost! I’ll let Isiah explain:

Bush was like I coulda used eyes like these back with my outfit in the 70s. Look at ‘em. They go on forever.

Minutes after the Pistons won Detroit’s first title, the celebration was marred with news that Pistons starting forward/center Rick Mahorn was selected by the Minnesota Timberwolves with Minnesota’s top overall selection in the 1989 NBA expansion draft. Detroit left Mahorn unprotected under assumption the nascent Timberwolves wouldn’t sniff the 31-year old’s contract, compensation incongruent with Mahorn’s declining contributions (seven points and seven boards in 1988-89).

Instead, the Wolves pounced, America watched a presidential press conference (hopefully not for the last time) enervated by trauma lingering from a recent NBA expansion draft.

Mahorn immediately got to work and by this I mean he told the Minnesota Timberwolves he would not come to work.

He was to be paid about $650,000 by the Timberwolves this year but wanted to renegotiate, saying he was losing bonuses and endorsements he would have made with the Pistons.

Minnesota took Mahorn in the expansion draft, but the team refused to renegotiate a contract that was to pay him $625,000 this season and $700,000 next season. Mahorn then traveled to Italy to have contract talks with the Verona team, which reportedly offered him $1 million for this season.

The Timberwolves gave up days before 1989-90 started, sending Mahorn to the Philadelphia 76ers, who renegotiated his contract, ballooning his expected $700,000 payment in 1990-91 to $1.33 million. He shoulda asked for two balloons.

Detroit freed Mahorn’s salary from its ledger and the NBA hoovered up a massive salary cap bump, $7.2 million in 1988-89 to $9.8 million per team in 1989-90. All sweatshirt, satin-jacket and VHS-tape revenue, too; the new TV deal didn’t kick in until 1990-91 (when the NBC cap jumped to $11.87 million per team).

Seeking steer, the Pistons looked up Koncak, a former top-five pick, restricted free agent and committed reserve. Averaged 4.7 points, 6.1 rebounds and 1.3 blocks in 20.7 minutes for the 1988-89 Hawks, the NBA’s seventh-slowest team. One-year deal, $2.5 million.

Since losing Rick Mahorn in the expansion draft, the Detroit Pistons have been seeking a starting power forward. Since the Pistons won the National Basketball Association championship in June, Jon Koncak, a 7-foot forward with the Atlanta Hawks, has been seeking a new contract, as a restricted free agent. So it was no wonder that the Pistons offered Koncak a one-year deal. What was shocking, though, was the size of the offer: approximately $2.5 million, according to a report yesterday in The Atlanta Constitution.

Koncak, whose salary last season was $675,000, is expected to sign the offer sheet. Then the Hawks will have 15 days to match the offer.

Jon Koncak, at $2.5 million? That’s literally more than Kevin Duckworth makes. Kevin Duckworth’s $2 million salary in 1988-89 made him the NBA’s fifth-highest paid player, tied with Michael Jordan, behind Patrick Ewing at $3.2 million, Magic Johnson at $3.14 million and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at $3 million in his final season.

August company, but that’s the NBA in summer, and the Hawks had until the first day of September to match the money. Koncak didn’t play exceptionally well against Detroit in 1988-89, but Detroit played six times a year against Atlanta, such was the familiarity before expansion. Undercutting the flailing Hawks was part of it, replacing Mahorn’s butt-first frame and superior no-stats defense was well worth the bread, especially for a single-season commitment. Detroit’s front office was well-aware of the NBC riches to come in 1990, the Pistons could replace Koncak with an inexpensive replacement the next offseason, or re-sign him to a more appropriate agreement.

Detroit GM Jack McCloskey swore hurting the Hawks wasn’t his motivation, even slightly.

McCloskey has declined to discuss his reasons. Several general managers have said it was done to put the Hawks, the Pistons' chief Central Division rival, over the salary cap and make it more difficult for them to obtain the outside shooter they sorely need. Teams are allowed to go over the cap, but they cannot make any moves until they get below the cap.

McCloskey, however, said that hurting the Hawks was not a consideration. He said that the Pistons needed another power forward to replace Rick Mahorn, also lost in the expansion draft. “I think it was a unique situation for us,” McCloskey said. “We really wanted a basketball player of his caliber. We wanted to make it difficult for (the Hawks) to match it. . . . We had quite a bit of money available under the new salary structure. I think we have been very prudent in our salary structure.

His best player agreed.

The Pistons insist they weren't deranged in their bidding, either. Even All-Star Isiah Thomas, who makes a paltry $1.1 million a year, understood the niche Koncak could fill. "I look at it this way," says Thomas.

In 14 years, the Knicks would hire the man behind the next quote to run New York’s professional basketball team.

"You're baking a cake, and you want it to be the perfect cake. The recipe calls for four cups of sugar, and you only have three. O.K., how much are you willing to pay for that fourth cup of sugar? Our position was he could help us win another title."

Koncak’s agent Steve Kauffman wasn’t buying the conspiracy chatter, not with Koncak’s sugar to sell:

“I’ve heard that (sabotage) talk, but I don’t subscribe to it,” Kauffman said. “It’s very Machiavellian in concept, but the thing that has not been noted is that the Pistons were not the only team willing to talk big dollars for Jon. The Pistons were able to assert themselves, and now all the other GMs are dumping on them.”

That lasted two weeks. The Hawks matched, and then they matched again. And again. And again, again, and again. Hawk GM Stan Kasten matched the first year, which was all he had to do, and inexplicably added five more at an average of $2.2 million a season, the number Koncak made in 1989-90. Kasten bargained $300,000 out of the first year, then added $11 million. Someone say it for me.

“I’ll say it for you,” Kasten said. “He is overpaid. Every player in the league should send him a bouquet, all right. Let’s face it, it’s something we’re going to have to deal with. “We have to go by whatever the system is. We intend to compete, we want to win a world championship. We have to take care and preserve our roster.”

Kasten has been defending his deal with Koncak all summer and is carrying that defense into fall. He has heard the grumbling from general managers in other cities. He has read their disparaging remarks in the newspapers.

Still, he maintains that he had no choice but to match Detroit’s offer sheet and work out a long-term deal so that the Hawks would not lose Koncak to free agency without compensation. If anyone is to blame, Kasten said, it is Detroit for making the initial $2.5-million offer to Koncak. “Once that happened, it changed everything in a lot of players’ and agents’ minds,” Kasten said. “The players are utilizing (Koncak’s contract), and you’ve got to deal with it. Every team has to confront it.”

Sometimes literally. Start with the champs.

John Salley, the Pistons' power forward and center, would eventually like a big-money deal, too. He says he has laminated and framed the newspaper article describing Koncak's contract.

King, shit.

"When I go into Jack McCloskey's office at the end of the season, I'm going to walk in and lay it down on his desk," says Salley, who must decide whether to play out his option next year; he is in the fourth year of a five-year contract for $2 million.

(The Pistons did not tear up Salley’s contract, he played out the $575,000 option in 1989-90, threatened to go to Italy, and re-signed with Detroit for $2 million a year for 1990-91 and 1991-92. “It was only a couple hundred thousand more,” Salley explained, “might as well stay in America.”

Understandably upset with still being paid less than Jon Koncak, Salley asked for a trade and received one, to Miami, at the NBA’s 1992 deadline. The Heat re-signed Salley to a four-year and nearly $10 million deal, though he was noted for a lingering bad check in 1992-93. When Salley joined the Lakers on a minimum deal, Shaquille O’Neal gave Salley a $70,000 loan and didn’t ask for repayment. I love John Salley, and Shaq.)

McCloskey, meanwhile, was honest in response to the Hawks’ largesse. Sending Jon Koncak $2.5 million is arguable but $13.2 million is laughable, which Jack presumably had to stop from doing when answering questions over Atlanta’s paperwork:

“Had we gotten (Koncak), he certainly wouldn’t have gotten that ($2.5 million) for the next five years. We would’ve gotten it down to a reasonable figure after that (first season).”

Hawk tutor chimed in:

"You just don't let assets of yours walk away and get nothing back for it," said Atlanta coach Mike Fratello, once Koncak was safely back with the Hawks.

Agreed. But about that extra $11 million.

Certainly the Hawks didn't want to see Koncak go to a team in their own division and have him come back and beat on them five times a year. But Fratello says that the Hawks needed him simply because he is "the consummate team player. He'll take a pounding, be our third or fourth scoring option, play team defense, hit the boards, change opponents' shots. Someday our Hall of Fame center [Moses Malone] isn't going to be here anymore, and Jon will fill in."

But that’s what 27-year old 7-foot guy Kevin Willis is here for, presumably with no new suspensions. In ongoing attempts explaining the rationale behind the NBA’s obsession with height, Kasten pointed toward The Board:

"You look at every freaking body you can over six-ten," he says. "Sometimes you do dumb things. God knows, I have. But in 20 to 30 years we'll have five seven-footers on the floor on one team.”

The 2009-10 Atlanta Hawks featured a stalwart 6-11 center in Zaza Pachulia and one 7-footer, Jason Collins, who worked 115 minutes as the Hawks won 53 games and made the Eastern semis. In 2019-20 the Atlanta Hawks featured 40 games of Alex Len and 30 of Dewayne Dedmon and then 2020 happened.

“Somebody will.”

Kasten could say this confidently knowing Don Nelson would probably have a job coaching at least one of the NBA’s many NBA teams in a decade, and between Hubert Davis and Michael Finley, Nellie was still a foot short even after starting Dirk Nowitzki, Shawn Bradley, and 7-foot Chris Anstey.

Stan wasn’t finished.

“Look at this." He points to a photo on the wall of his office: It shows him standing next to somebody who looks like a giant Baby Huey.

"I'm not a [small person]," says Kasten. "That sucker is huge!"

Who is it? It's a prospect, one Jorge Gonzalez from Argentina—7'6½", 403 pounds. Kasten had him tested. Gonzales is not a pituitary giant; he's just huge.

"Can he jump?" asks Kasten. "No. Why should he? He can dunk standing."

Jon Koncak’s contract is how I learned about Giant Gonzalez, the seven-and-a-half-foot pro wrestler:

On a blackboard Kasten has the names of other prospects, big men mostly, from nine countries. An NBA team will do a lot to find, hire and keep a big man.

"We spent more than we should have for Jon," says Kasten. "That's as far as I'll go. I had to confront the options. And what it comes down to is, the roster is always more important than the payroll. We want to win."

The NBA was on everything that sold in the late 1980s. This money had to go somewhere and, Kasten argued, the salary cap kept things in check, so to speak, in a league where a single player means everything.

Kasten said: “Without it, we’d be paying a whole lot more. This way, it’s based on revenues.”

Without it, leverage for the gnarliest word in bargaining, a term so malevolent they banned it from NBA front offices. Renegotiations.

“I remember being a guest on a cable show right after Magic signed that original $25-million contract spread over all those years,” Steve Kauffman said. “I said on the air …”

Through the cable, Steve.

“[…] that when you look at the inflation rate and the rising salaries, he’d be dramatically underpaid in a few years. Now, he’s renegotiated a couple times.”

Steve, that is prescient, but if you were already appearing on cable shows in 1981 you should have invested way more in cable television than in percentages of Jeff Hornacek’s contract.

Before they banned renegotiations, and after Koncak’s agreement, the agents got to work. Workers took more for their work, starting with the worst of them:

Fallout first hit in Utah, where Karl Malone, the All-Star power forward for the Jazz, demanded renegotiation of a 10-season, $18-million contract he had restructured just the season before.

Did the Koncak signing influence his decision?

“Blank, yeah,” Malone told Utah writers. “I would say hell, yeah, but I know newspapers don’t like that.”

In Philadelphia, when 76er forward Charles Barkley learned that Koncak will earn $600,000 more than he would, despite averaging 21.1 fewer points, he also demanded renegotiation. He got it, too. Barkley’s five-season, $9.4-million deal was restructured to $19 million over six seasons. The 76ers also have the option of an additional three seasons for $10.5 million.

The outspoken Barkley, talking on a Philadelphia radio show last summer, had this to say about Koncak’s contract:

“It’s unfair for a guy to be making a million and a half more than me, especially one who can’t play. If Michael Jordan is making more than me, I can shake his hand. But if Jon Koncak is making $1.5 (million) more than me (over the contract’s length), we’ve got a problem.

“If I average four points and six rebounds, I’d get killed. This man gets a $2.3-million raise for averaging four points a game. If he’s getting $2.5 million for four points, I should average 2.4 points and the Sixers would be getting their money’s worth.”

Koncak, in an interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, responded: “Charles should be grateful. He made a lot of money off my deal, and he was not a free agent.”

Other renegotiations followed. Houston center Akeem Olajuwon, for example, received a raise from $1.7 to $3 million. Rick Mahorn’s impasse with the Minnesota Timberwolves, however, was only partially affected by Koncak’s deal.

Clipper center Benoit Benjamin said he attempted to use Koncak’s contract as a barometer of his worth. Before Benjamin made his brief stopover in Italy, he complained at a press conference, “I couldn’t even get what Koncak got.”

Well, yeah, millions and millions for some but not Benoit Benjamin, this isn’t anarchy. This isn’t Italy. I don’t see Camillo Berneri, do you see Camillo Berneri?

Atlanta took care of business, too, re-doing Dominique Wilkins’ deal:

Koncak's contract, combined with a $14.5 million, five-year contract extension for Dominique Wilkins, has increased the Hawks' payroll to $10,600,000, third highest in the league, behind the Knicks' $12,200,000 and the Portland Trail Blazers' $11,200,000.

Small market teams take all sorts of flak for big salaries but nobody ever talks about the money New York and Portland spends.

Portland coach Rick Adelman called the deal ludicrous, and Golden State general manager and coach Don Nelson said there "must be some sort of war between Atlanta and Detroit."

Rick Adelman’s Trail Blazers paid a third-string center (Wayne Cooper, still playing in 1989-90) a million bucks the next season, he owns no room to call anything “ludicrous.” Speaking of Atlanta, Don Nelson again confused the War of 1812 with the American Civil War. I don’t see Isaac Brock, Nellie, do you see Isaac Brock?

"It's a whole new world out there when it comes to money," Cleveland vice-president and general manager Wayne Embry said. "And it's pretty scary."

Eight weeks after this quote, Wayne Embry traded Ron Harper and two first-round picks for the right to give Danny Ferry a 10-year, $34 million deal. Scary? Horrifying.

Said Magic Johnson: “As long as the league’s (popularity) goes up and the gate goes up, the players are going to benefit. If it maxes out, it maxes out. But right now, the league is more popular than any other league. They’re making a lot of money.”

David Falk said: “While I am a neo-capitalist who wishes there were no restrictions at all, I think the cap has been a cohesive device that has given the league a perception of stability publicly, which is partly responsible for its growth.”

I was incapable of addressing Falk’s salary cap point with any clarity after reading use of the phrase “neo-capitalist.” Hammertime had a lot of people hiding under banners.

Hilariously, the Hawks matched Koncak’s offer two weeks before the NBA’s showy annual meetings, a lot of meat for late September:

The National Basketball Association conducted its annual meetings here last weekend, and the league`s top officials weren`t that concerned with the invasion of foreign players, the defections to Europe of Danny Ferry and Brian Shaw or the zone defense, basketball`s version of the balk.

No, they wanted to talk about Jon Koncak, who has become basketball`s version of the wild pitch. At least that`s what everyone felt the Detroit Pistons uncorked this summer when they offered the Atlanta Hawks` backup center a $2.5 million, one-year contract.

Had Koncak signed, this season he would have earned as much as Michael Jordan, who signed an eight-year deal a year ago.

”He just took advantage of the system. He was in the right place at the right time,” said NBA Commissioner David Stern.

His coach may argue against the commissioner’s point:

Jon Contract? He got it.

"Hey, I can't justify what they offered me," he says with a careful shrug. "But what was I supposed to do? Say no? The league is changing. I think maybe this is just the start."

"Thirteen million," says Koncak softly, still amazed. "Thirteen million!"

Opponents were awful aware of that number by exhibition season:

[Utah Jazz center Mike] Brown pins the ball against the glass and hits Koncak with a body check that sends the seven-foot, 260-pound center into a spinning, flailing arc toward the Omni floor. Koncak lands on his back with a resounding thud. The crowd gasps. It appears that Brown mutters something as Koncak lies writhing. Slowly Koncak rises, limps to the free throw line and shoots two free throws, missing each badly. He calls timeout and with the help of the trainer staggers to the training room.

Is Brown angry about Koncak's newfound wealth, about the 26-year-old's recently signed six-year deal with the Hawks for an astonishing $13.1 million, or is this your basic NBA territorial how-de-do?

"Just a foul,' " says Brown later. "Just bodies going in opposite directions."

Philip Bailey, are you writing these lyrics down?

As Mike Brown dresses in the Jazz's locker room, he says that he isn't jealous of Koncak, and he seems to mean it. "I'm happy a young man with a family can make that kind of money," Brown says. "I have three or four millionaires on my team already. In two years I'll be a free agent, and if it's meant to be, I'll get mine. Jon's salary helps us all."

"A backup center helped everybody," says the Hawks' Dominique Wilkins, one of the league's superstars. "I can't feel jealous. There's no question he helped my contract directly."

Did it help the Hawks? The frontcourt was stacked: Kevin Willis missed one game in 1989-90, same as Moses Malone. Koncak battled injuries (3.7 points per game in 18 minutes a night, 4.2 rebounds), missing 28 contests, but big forward Cliff Levingston played 75, and center/forward Antoine Carr played every game until he was dealt midseason to Sacramento for Kenny Smith, two days after Kenny did this:

Why did the Hawks need Kenny? Because Hawk point guard Doc Rivers was either playing-through or missing games due to groin injury in 1989-90. The Hawks rallied with Kenny, 19-16 after the trade, but finished with a 41-41 record, outta the playoffs.

The team couldn’t even blame Reggie Theus, selected a spot behind Rick Mahorn in the 1989 NBA expansion draft by the brand-new Orlando Magic.

Detroit? The lineup with James Edwards, Bill Laimbeer, Mark Aguirre, John Salley and Dennis Rodman and 7-foot William Bedford (“if he gets over his drug problems”) realized it probably didn’t need another large fella. With its salary cap surplus, the Pistons signed Scott Hastings for $450,000, Scott played 166 regular season minutes and the Pistons won another title in 1990.

Koncak was the NBA’s 11th-highest paid player in 1989-90 at $2.2 million. The Hawks refused to blame Jon nor injury, firing Fratello hours ahead of the 1990 playoffs. Kasten chose decade-long power forward resolution Tyrone Hill with the No. 11 pick of the 1990 NBA draft but dealt him to Golden State for No. 10 pick Rumeal Robinson. Atlanta stayed resoundingly healthy in 1990-91 and still only won 43 contests under new coach Bob Weiss, Koncak (at $1.55 million, the deal’s dimmest output) was the NBA’s 48th-highest paid player.

Defense was a problem, Wilkins and Rivers aging, sixth man Spud Webb relatively surmountable, Rumeal a rookie. Short-armed Willis and block-per-3.5-fouls Koncak presented an awfully porous middle. The interior remained unrelieved with 82 games of 35-year old Moses Malone off the bench, constantly adjusting those goggles. The Hawks made the playoffs in 1990-91, losing to Detroit 3-2 in the opening round.

By 1991-92, Benoit Benjamin made more than Jon Koncak.

The Pistons traded Rivers at the 1991 NBA draft to the Clippers for lottery pick Stacey Augmon (yep) and Spud Webb to the Kings for 1990 lottery pick Travis Mays (nope). Atlanta traded its first-round pick (Anthony Avent) to the Nuggets for re-signed 7-footer Blair Rasmussen, who was sort of like a Jon Koncak that didn’t drop passes.

Blair led the NBA in turnover percentage in 1991-92 with only 51 miscues in 1968 minutes before retiring with a spinal injury in 1993, possibly incurred during this attempt at celebration with detente-minded Hawk teammate Alexander Volkov:

The 1991-92 Hawks won 38 games and missed the playoffs, but luckily the Nets traded Mookie Blaylock to Atlanta a week into 1992-93 (for Rumeal Robinson).

Blaylock’s presence and an ascendant Augmon led the Hawks back to the playoffs, Koncak averaged an impressive 3.5 points in 25 minutes a game. Jon started 65 times in 78 appearances alongside Kevin Willis as the Hawks continued to rank among the worst NBA teams at defending basketball shots. This mark recoiled, severely, in 1992-93, the Hawks jumping from 26th out of 27 NBA teams to No. 7 in eFG defense under new coach Lenny Wilkens.

The Hawks traded Dominique Wilkins partway through 1993-94, adding Danny Manning, remaining the defensive powerhouse, losing in the Eastern semis to Indiana. Blaylock was third in the NBA in steals but whistled for only 144 fouls in 81 games, 2915 minutes. Koncak (at the high-water mark of his contract, $2.9 million, the NBA’s 31st-highest paid player in 1993-94) cut back on his whacks and remained a starter alongside Willis.

The four-year partnership ended two games into 1994-95, Willis moving to Miami in a deal for Steve Smith. Jon Koncak was now the only Hawk remaining who knew what the top of Mike Fratello’s head looked like. Lenny Wilkens replaced Koncak with Grant Long as power forward, Andrew Lang’s immaculate sense of spacing took over at center.

This was the final year of Koncak’s contract, and at $2.6 million, JK ranked third on the 1994-95 Hawks’ payroll behind Hawk free agent signee Craig Ehlo ($2.65 million) and the long-retired Rasmussen ($2.75 million).

The Hawks and Koncak took an opening round bow to Indiana, swept, the contract was done. Seventy-five NBA players made as much or more than Jon Koncak in 1994-95.

This figure was about to rise. The salary cap rose from nearly $16 million in 1994-95 to $23 million in 1995-96 due to expansion payouts, but in 1995 David Falk led what I’m guessing was a “neo-capitalist” takeover of the union’s side of labor negotiations with the NBA, which, as you’d guess, absolutely destroyed the NBA’s middle class.

Middling free agent players — Jon Koncak ($1 million with Orlando in 1995-96, started most his regular season and three playoff games while Shaq and Horace Grant traded injuries), Rex Chapman (Suns starter and supreme sixth man, playoff hero, $574,200 combined in 1996-97 and 1997-98) and Tyrone Corbin (lead swingman defender in Atlanta, double-figure scorer, same terms as Chapman) — signed for the least amount allowed by the new Collective Bargaining Agreement. The fourth and fifth-best players on NBA teams in the late 1990s sometimes played for what the sixth and seventh-best players worked for over a decade before.

The two-year deal Koncak signed with Orlando in 1995 had a season season in 1996-97 at $1.15 million. Koncak made camp with the recently Shaq-less Magic but was traded to Golden State in a package for famous Shaq replacement Rony Seikaly. The Warriors cut Koncak, which at least saved Jon from wearing those uniforms. He retired, making over a million bucks not to play in 1996-97, about as much money as Koncak (the No. 5 pick in an NBA draft) combined to make in his first two seasons.

Happy endings, right? We’re getting there. The problems started upon the contract’s agreement in 1989:

He has had to change his phone number a couple of times to keep the investment guys and money leeches from hounding him.

Good start, noble ideas for the future:

So does Koncak, and as he thinks now about his future earnings and his current good fortune, he states firmly that there is some real responsibility that comes with big money, above and beyond elbowing for position in the lane. "When my career is over, I may work for a charity or with the community somehow," he says. "I have a responsibility to give back, and I will do that. I have to."

What’s on record, sadly, is Koncak testifying in a fraud trial two decades after his NBA career gracefully concluded. Koncak lost about the total amount of his five-year rookie deal on an amusement park scam.

The FBI had a dumb name for it: ‘The Disney Resort that Never Was.’ The investors called it ‘Frontier Disney,’ and Koncak was instrumental in delivering swindler Thomas W. Lucas Jr. to justice.

Koncak, who played for the Atlanta Hawks for a decade, said the more than $2 million he lost was used to pay for land option contracts. The option fees gave him and other investors the right to buy the land for a specific price before a certain date -- usually between 30 and 90 days.

Koncak said the plan was to sell those option rights to developers after Disney announced its plans to build a theme park near Celina [TX]. But that never happened. The announcement kept being postponed, and the options eventually expired.

"The funds we put up weren't ours anymore," Koncak said.

About $45,000 of that was from a college fund for his two daughters, he said. It was supposed to be their investment.

[Koncak’s pal and business partner Jon] Yarid said Lucas provided all the inside information about the theme park, from a secret source.

Prosecutors say Lucas' source never existed -- that he made up all the elaborate development plans to dupe investors.

Retired basketball star Jon Koncak, an old SMU buddy of Yarid's, was one of the investors who lost money, prosecutors said. The former SMU and NBA center put money into a 1,061-acre parcel with water and sewer connections, Yarid said.

Koncak, who is expected to testify this afternoon, planned to flip it to developers after the Disney announcement, he said.

Yarid, who was an SMU swimmer, said other college friends he got to invest also lost money.

Some of them gathered at a University Park home to watch the 2007 Super Bowl and await the announcement in the form of a TV commercial, he said.

When the game ended, there was dejection in the room, as well as the leftovers of a Mickey Mouse cake.

"It was such a big, big downer," Yarid said.

As Bears fans, we thought we had sad parties that Sunday. We did not have the saddest. Only some of us expected a Disney ad to be the highlight of our night.

The bad guy got a whole 210 months.

Thanks for reading! I wondered where Detroit got the cap space to sign Jon Koncak and here we are. Enjoyed my work over the years? Consider keeping me going, the 2024-25 NBA season previews are next:

Ever wondered how a certain team got where, a long time ago? Hoops Analyst is where I typically end up, my favorite site for over two decades. We don’t have room for video but I do have the ‘Hill St. Blues’ theme in my head because I just told my cat to “be careful out there.”

Maybe my very first sports memory as a child: hearing Atlanta old guys complain about this contract. Thank you for this post

*I struggled on "Hammertime" style, "Hammer-time" or "Hammer Time" or "Hammertime." When I imagine Kramer saying it to Jerry, though, it's HAMMERTIME.

**The John Salley interview talks about Shaq not cashing his NBA checks, this is the first I've heard of this and an old Lang Whitaker interview with Shaq in 2006 kinda confirms that Shaq is the Jay Leno of Dunk dot net.

***I also highly recommend googling "patricia nba site" for all sorts of 1990s goodness, it was a major asset in the late 1990s at OnHoops.

****I threw in "JK" and I think one "Jon Koncak" but am proud of myself for eliminating needless barbs like Jon Konhack for the fouls part or Jon Hancak for when he signed his name.

*****My favorite video is the clip of fouls from 1991, worryingly satisfying.

******At one point in the process I found myself trying to explain Jeff Ruland to the imaginary Donald Fagen always looking over my shoulder. The best I could do was tell Donald that Jeff Ruland looked like all four members of the band Alabama put together, which is something someone can do even if they don't know what any of the guys from the band Alabama book like, like Don and myself. "All four members of Alabama put together and about 7-foot, 290." And the various facial hair in front of Jeff -- mustache, beard, goatee in the 1990s -- all can be explained by the four Alabama members, also going through the same stylistic shifts.