When John Starks beat Don Nelson at the game of 'New York'

(This email was originally sent to subscribers in Aug. 2018.)

“To Cark.”

That was the joke.

John Starks was so dumb at jump shots that he had to be dumb at life, too, to the point where a name like “Cark” would make sense to John.

Starks’ prevailing mixtape of misguided motivational maneuvers — head-butting Reggie Miller, jawing at officials, looking off Patrick Ewing’s screens even after New York’s decelerating center shuffled affreightment duties toward his excitable teammate — those weren’t enough.

John Starks had to pay, in public, for the image he’d created for himself. Don Nelson wanted to make sure of it.

The Undefeated’s Mike Wise, who covered the NBA for the New York Times in the 1990s, detailed Nelson’s setup. And punchline.

While coaching the Knicks for an abbreviated 59 games in 1995-96, Nelson told me a story involving John Starks. He said a fan approached the former Knicks guard after a game and asked him to sign a pennant for his brother. “His name is Marc. Marc with a ‘C.’”

When the fan got the pennant returned, Nelson said, it read, “To Cark.” Marc with a “C,” get it?

Nellie delighted in telling that story, prefacing it with, “This is how stupid John Starks is.”

He wanted Starks traded and was prepared to give up any information that might lead to that end.

At least someone got an end out of it. Nellie couldn’t get to Game No. 60 in New York, failing to adjust to a city that demands constant reexamination.

The Knicks fired Nelson long before they got rid of John Starks because John Starks was always a New York Knick, always gonna be a New York Knick.

Don Nelson was just another coach.

Knick saviors are hired because of their poison, because of the breed and alignment that make the names so suitable at the time.

From Willis Reed’s ascension to Red Holzman’s return, Isiah Thomas’ tip-sheet to Larry Brown’s throttle, there’s always a chance, always a reason why it should work. Rick Pitino had the advancing roar of the 1990s at his back right before his hack stopped short, Stu Jackson stood with the support of the league’s office at his side and Hubie Brown could carry 50 times his own coaching weight. Phil Jackson was only perfect.

Each of the routines carried a kernel of basketball truth, something that was gonna return New York what it was owed. Every one of those failed dignitaries clucked with selling points that chatted well past the lifespan of the glowing globule of consumer confidence that name recognition always inspires.

Don Nelson was as good as any of New York’s hires, just as hopeless in retrospect as any other contender in this exasperating canon. He was a forward-thinking iconoclast, a teammate of Bill Russell’s and a player’s coach — the sort of brain to take over a weary group of vets and quirk them into something more compelling.

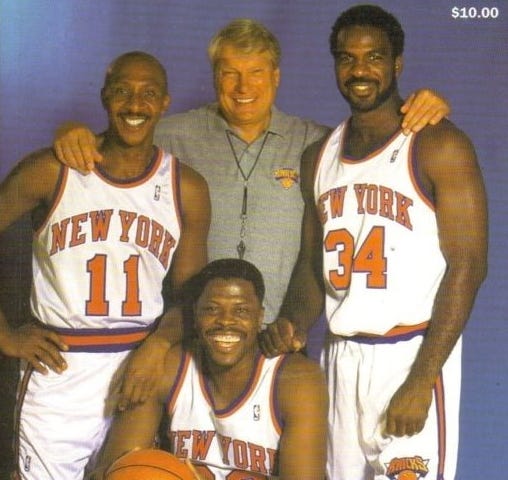

Pat Riley was New York’s coach before Nelson and he’d done all he could with the aging crew, resigning via fax for the favor of a blank slate in Miami in the summer of 1995 ahead of the Knicks’ declining years. Riley’s abrupt departure was all the writing that Patrick Ewing’s 33-year old wall needed, Charles Oakley (32 in 1995-96) and Derek Harper (34) read as well as anyone and New York needed someone to release that tension.

In stepped Nellie, to peel back from three-hour practices and celebrate the promise of Anthony Mason, a point forward apsatively made for the decade he did best. Mase was a CBA call-up turned crucial, 1994-95’s Sixth Man Award winner, a 28-year old about to hit his prime. Nelson wanted Mason as his point forward.

The Knicks had no cap space after Riley left, there was little reasonable trading interest in any part of the club’s 55-win roster, any fulfillment was going to have to spring from the inside-out. The Los Angeles Lakers made the 1991 Finals in the first year after Pat Riley’s hop out of Hollywood, sloping in under player-turned-coach Mike Dunleavy, functioning gleefully with Magic Johnson throwing pinpoint passes to spot-up shooters and determined finishers.

The Knicks owned approximations of these same tools. They hired Nellie for 1995-96 and beyond, three years and $5.5 million with two seasons guaranteed.

Nelson was fired by the Warriors as play-caller and president midway through 1994-95 and by this point Nellie was as much Victor Alexander’s coach as he ever was Russell’s teammate, but he also felt like an answer. Nelson even worked with John Starks before, giving the eventual Knicks All-Star his first shot as an NBA rookie in Golden State.

“It’s funny how paths cross again in this game of basketball,” Starks reminded Mike Wise, days before 1995-96 began.

“I began my career with him and now we’re reunited again. Of course, I’m a much better and more mature player now than I was then.”

John Starks was working as a roofer in 1988 when he turned down a $10,000 to play in Larry Brown’s first training camp as head coach of the San Antonio Spurs. Nelson, then running the Golden State Warriors as president and head coach, tabbed Starks with a minimum deal soon after.

Nelson advanced John a two-year deal initially, “but I didn’t want to play for the money he was offering,” Starks revealed in his 2004 autobiography, My Life.

“We were at serious odds.”

Starks took the minimum for a year and a seat next to his Golden State teammates, playing all of 316 minutes in 1988-89. “Nelson has a huge ego,” the bio wrote, “and I crossed the line with him by not signing the contract. From then on he made it terrible for me by sticking me on the bench and not playing me.”

John did argue on his benefits’ behalf, entering Nellie’s office at one point in his rookie season to complain about not “getting enough playing time.”

Minimum salaried-dudes weren’t supposed to be seen, certainly not viewed while outlining a determined opinion, 1989’s rookies were only supposed to be a rumor at the professional level. Don Nelson was purportedly a player’s coach, to that point, but the 1980s were about to turn into the 1990s.

“He probably looked at me like ‘this guy has some nerve,’” Starks recalled in 1997.

“I think he took serious offense to that.”

The Warriors declined to bring Starks back for 1989-90, anticipating Tim Hardaway’s rookie season, Nelson advised John to work on his ball-handling and shooting ahead of what was certain to be his NBA return.

“When Nelson cut me,” Starks noted in 2004, “I told him, ‘Thanks for giving me the opportunity to play in the NBA,’ and I meant it.”

Starks spent 1989-90 in the CBA, making $600 a week for the Cedar Rapids Silver Bullets.

The offseason saw Starks sharing the court with the Memphis Rockers, the mid-south’s single-season inclusion into the World Basketball Association, a league which refused entry to players above 6-5. John also augmented his minor league basketball income by working as a grocery store bagger for $3.35 an hour until 1991, when the U.S. minimum wage was advanced to $3.80 an hour.

Starks acknowledged that he lost at least one major league opportunity after a row with a referee resulted in a CBA suspension, but that may not have been the end of it.

“I had the feeling,” Starks told Spike Lee in 1997, “Nelson put the bad word out on me.”

In 1990, Starks caught the eye of New York Knicks GM Al Bianchi. Starks and his wife drove a blue Mercury Cougar from Tulsa to NYC in time to meet a New York Knick training camp.

“He didn’t do everything right,” Bianchi compiled later, “but he wanted it.”

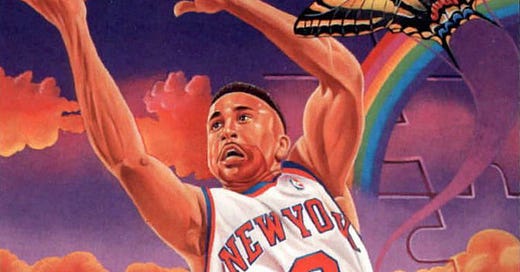

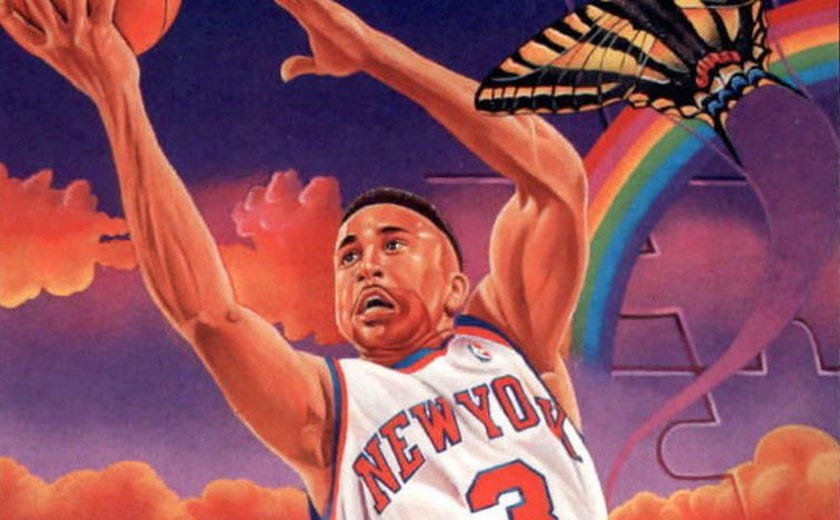

THREE TIMES STARKS TRIED TO DUNK ON PEOPLE

John Starks tried to dunk on Magic Johnson during John’s first NBA preseason in 1988.

“I came down on a two-on-one fast break and Magic was back. I had Tellis Frank on my left-hand side. I dished the ball to him and he made the dunk. I came back down on the same deal, the same exact play, and this time I said to myself, ‘I was going to go over the top of Magic.’

“So I went up to dunk on him and he reached up and caught me in midair. Magic was six foot nine and 240 pounds, a strong man, he got called for the foul and was shocked. I was shocked I’d missed the dunk.”

At the next break, Don Nelson called Starks over to the Warrior huddle.

“After the play, Nellie told me, ‘go over and thank Magic because he could have ended your NBA career right there.’ So I went over to Magic and thanked him.”

John Starks also tried to dunk on Patrick Ewing during John’s first training camp with the New York Knicks in 1990. “I needed to impress the coaches.”The Knicks were thick with guards. “The only way I had a chance to make the team,” Starks decided, “was to do something spectacular.”

Ewing blocked the stuff, sending the guard to the floor in a crumple on the follow-through, spraining Starks’ right knee.

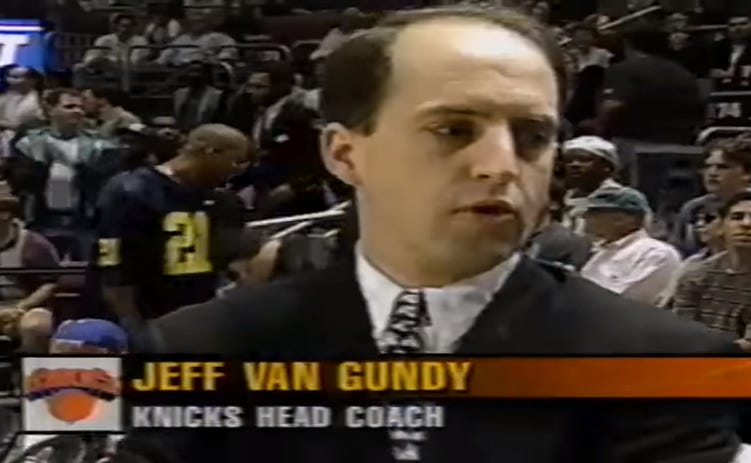

“He had no idea,” assistant coach Jeff Van Gundy said later, “he was going to be cut that day.”

League rules prevented teams from waiving injured players. Starks twisted his way onto the Knicks.

“If I hadn’t tried to dunk over the franchise center on the last day of practice in the final minutes of a scrimmage, I would have been toast.”

In 1993, Starks would go on to dunk over Chicago Bulls forward Horace Grant.

Those were the three times Starks tried to dunk on people.

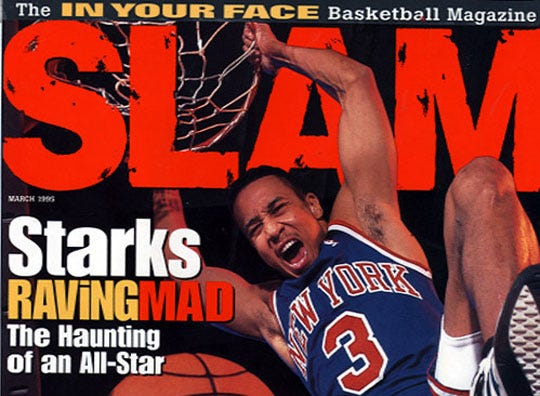

“Everybody thought he’d be a good coach, but sometimes nightmares happen.” — John Starks, February 28.

The Knicks won 10 of 12 to start 1995-96, running an orthodox lineup with Starks at off guard alongside Derek Harper; Patrick Ewing, Charles Oakley and Anthony Mason frightened the frontcourt. Mason worked 52 minutes in the team’s third loss, an overtime battle against Atlanta, the next night’s trip to Charlotte resulted in a defeat but New York righted its rain after Thanksgiving, winning three in a row.

Starks scored 25 points on 9-12 shooting in the end to that streak, a seven-point loss in Chicago on the second night of a back-to-back. Starks helped hold Michael Jordan to 8-27 shooting.

New York was at 17-6 when Miami came to town on Dec. 19 and 18-6 after Pat Riley’s new team left Madison Square Garden, the Knicks held the Heat to 70 points while fans held disrespectful signs in back of Riley’s new bench in Pat’s return to New York.

“This was a game that, more than anything, we’re glad to have over,” Nelson concluded after the win. “We can start concentrating on games at hand and do what we’re supposed to do as basketball players and coaches.”

Starks, Ewing and Harper all hugged Riley just prior to the game’s tip-off.

“Right after that,” Starks said in his book, “Nelson started playing mind games with me. Like taking me out of games I was doing well in and putting me into games but not running any plays for me.”

The Knicks fell in nine of 15 games following Riley’s return to New York, losing in New Jersey, at home to a team from Sacramento, and against an expansion club from Vancouver.

“In the past, we've always kicked butt and taken names,” Ewing lamented. “Now it's the other way around.”

In February, Nelson tried Starks as a sparkplug reserve — fielding a massive cluster of Ewing, Oakley, Mason, Harper and 6-10 Charles Smith in a loss to Orlando.

Shooter Hubert Davis (47.6 percent from long range in 1995-96) eventually replaced Starks (36.1 percent) in the Knicks lineup, ending John’s legendary, 36-month run at New York’s starting shooting guard position. East-leading Chicago took a 42-5 record into the All-Star break, New York took a 4-10 turn out of it.

“Basically, everyone here is kind of associating it with the coach, Don Nelson,” John Starks’ sister told the New York Post in February.

“I don't think they ever got along from the beginning. I heard they're not even practicing hard. It's like they're in high school. They just sit around and play.”

Starks’ 74-year old mother also chimed in.

“I wish [John] would get out of New York. The whole family does. We don't want him wasting his time there.”

Post reporter Thomas Hill was trusted with Starks’ family contact info earlier in the season to write a puffier piece on John, and these updated remarks unsurprisingly went unappreciated by the Knick guard.

Hill was met by Van Gundy’s voice at the outset of New York’s next media availability, the end of a practice. The assistant shouted a few appropriately snidely remarks in the reporter’s direction, inspiring second-year Knick Monty Williams to take issue with a note the Post writer published on the 24-year old forward earlier in 1995-96.

Starks took over from there, loudly. Hill was emphatically asked to never again phone any members of the Starks family.

“You don’t call a 74-year old woman,” John said a day later, “about what’s happening with the Knicks.”

“We’re no powerhouse, that’s for sure. Cleveland beat us, Portland beat us, New Jersey beat us.” — Charles Oakley, January 13.

Hours after Oak’s quotes hit the newsstands, Sacramento beat the Knicks in New York. The Knicks were slipping in the Eastern order.

Mason thrived in a starter’s role, working up nearly 3500 minutes in 1995-96, but Nelson’s brand of whatever had turned Mase off.

“When we don't establish an identity, you never know what we're going to do, I don't know what's going on,” Mase admitted midseason.

“We finally get a team that plays post-up, and we play less post-up than any other game. When we play a team that doesn't let us post up, we try to post up all day. That's the damn play calls.”

(These comments also came before the Tyus Edney-led Sacramento Kings scored 119 points in Madison Square Garden.)

Knick president Dave Checketts admitted to feeling “anything but very disturbed, and distressed” with his club’s 1995-96 turn under Nelson. Rangy 25-year old swingman Doug Christie, a future Jordan stopper and sure starter on most other Nellie-led clubs, worked only 215 minutes for Nelson before he was dealt to Toronto for Victor Alexander.

The Knicks were shopping for offseason cap space. “If I’m here, I’m here,” flighty forward Charles Smith remarked in January. “If I’m not, I’m not.”

By February, he was not — dealt to San Antonio with Monty Williams in exchange for expiring contracts.

On Feb. 25, deep into a loss in Phoenix, Starks and Nelson shouted at each other on the sideline. “Put a fork in those brothers,” Charles Barkley concluded after the nationally televised defeat. “They’re done.”

On Leap Year’s Eve, 1996, Starks discussed in detail the Nellie “nightmares.”

“He feels I can’t do the job,” Starks told the New York Times, digging in on his coach. “That’s his opinion.”

Starks was not only coming off the bench behind Hubert Davis, but the Knicks coach had also begun benching Starks and Derek Harper in the fourth quarter of games.

“I need Hubert on the court a lot,” Nelson explained.

“Sometimes it’s business, and sometimes it’s personal,” Harper offered. “In this case, it could be both.”

Starks met with his coach several times to air out differences.

“I know what I can do if I’m given the proper time. Over the last few games, I’ve been trying to show him. But it’s all for nothing.”

Nelson remained unmoved.

“I'm not going to be intimidated by John, or by the newspaper coverage, or by whatever tools the players use to put pressure on me,” the coach insisted as March began.

“I’ve got to get Hubert more minutes.”

The MSG crowd began booing the head coach during player introductions. Starks described his rift with Nelson as “unhealable,” signing off on his 1995-96 season with months left to play.

“You can never heal the hurt. The hurt will always be there. It will not be healed.”

“I don’t know what the hell is going on.” — Anthony Mason, March 1.

The Knicks fired Nelson on March 8, hours ahead of a loss to the Philadelphia 76ers, he’d escape his New York Turn with a reported $4 million to take home to Maui.

Assistant Van Gundy took over the 34-25 team, dropping the game against the 76ers before turning the twist long enough to destroy the Chicago Bulls on NBC in his second game as an NBA head coach, running Chicago’s record to 54-7. The 32-point splat was the largest defeat in Chicago’s 72-win season.

“Right now, I’m the coach of the Knicks,” Van Gundy struck. “They didn’t say ‘interim.’”

A day after the win over Chicago, ex-coach Nelson visited with the media “for 45 minutes at Mickey Mantle's restaurant after receiving the Award of Courage from Sloan-Kettering.” It was Nellie’s chance to explain himself after losing three gigs in thirteen months.

“There isn't anything I didn't like about New York except for the team,” Nellie clarified.

“I thought the team was old and needed change. I tried to change it philosophically and it didn't work. It’s a very difficult team to coach.”

The fading Knicks under Nellie weren’t too far off from what Pat Riley skulked around with the season before. The pace was about the same, defense still in the top five and offense huffing below par, misses wheezing with increasing regularity. Straight paper suggests the 1994 Eastern Conference champions took an undramatic, anticipated dip.

The right coach could have found a way to handle the other end of that hill, even with pride coming up the backstretch, minding a self-examination season without riding the brake pedal.

Nelson hoped his favors would do the work, he couldn’t understand why his players would treat him so thoughtlessly.

“I was always amazed that Mase wasn't happier,” the 55-year old explained. “I don't know why he wasn't happy. He knows that I respected him and I gave him the ball a lot. I gave him a lot of freedom, but he still wasn't happy.”

Nellie lamented his cool relationship with Charles Oakley, and a whiff on a trade that would have sent John Starks to San Antonio for hybrid guard Vinny Del Negro.

The deal “was a no-brainer,” Nellie told the assemblage at Mickey Mantle’s. “It would have alleviated all the problems with John had he been traded.”

It was clear that Nelson felt as if he had a unerring read on exactly what was best for Starks.

“John doesn't like me, but that's okay,” Nellie offered.

“I understand John. I know who he is.”

Before flipping five time zones, Nellie reflected upon the fissure that was every bit the fault of Generation X.

“I've always told my players that when things go wrong, the first place to look is in the mirror. And I want to be the first to tell you that that's exactly where I looked after being released from my job.

“I have to decide why I've been fired twice in two years what I'm doing wrong, what changes do I need to make as a coach and as a person to get the modern-day player to play harder and more consistently.”

It was assumed for years that Don Nelson had no idea how to use a mirror, now the papers had proof.

“But don’t feel sorry for me, I’m getting paid.”

The Monday was the work of a man who had been forced to give a speech three days after being fired from three jobs in 13 months. Anyone else in the room ever have to coach John Starks, twice?

“I was the wrong guy for the job. I thought I was the right man, but it didn’t work out.”

Van Gundy’s 32-point, national television debut was no joke.

The Knicks ran only 13-10 in the remaining regular season under JVG before falling in five in the Eastern semifinals to Chicago, but New York played the Bulls tougher than anyone else in the 1996 playoffs, more consistently than younger outfits from Orlando, Seattle, and Miami.

That’s the problem with movements, they’re usually derailed by the pound of flesh stuck behind the wheel.

Nellie’s plan, he declared in 2007, was to disrupt the Knick foundation in ways that ran well beyond thrashing about with John “the Cark” Starks. Four years before New York dealt Patrick Ewing to Seattle for a package returning 33-year old Glen Rice and 25 games of Luc Longley, Nelson wanted the Knicks to think bigger.

“I had coached Shaq in the World Championships in ‘94 and established a pretty good relationship with him,” Nelson told Harvey Araton in 2007. “I knew he wanted to go elsewhere and I brought this up in a meeting with the Garden people.”

Shaq was a free agent at the end of 1995-96, the Knicks were even ahead of the Los Angeles Lakers in the race to clear cap space for the 1996 offseason. Nellie wanted an advance on conditioning O’Neal to last a Knick.

“I said: ‘He would come to New York. It’s going to be Los Angeles or us. And if we give ‘em Ewing, it would be the best deal Orlando could make.’

“Well, somehow that got back to Ewing and after that, I’m toast.”

New York is the sort of collection that lends you taintless hindsight even before you’ve noticed that the rear view is missing and that the AC doesn’t work, the guy told you the AC in this thing worked, placing the pin on Ewing in this callback doesn’t give anyone enough credit.

Including Nellie. He had the right ideas.

The Knicks had no shot-creators, the team won 55 games under Riley in 1994-95 with a mediocre offense and then everyone got a year older. Not only was Anthony Mason the closest Knick to his athletic prime, he was the team’s most creative passer and the only rotation member that could handle the sort of minutes needed to ride out a successful regular season.

New York couldn’t afford to hit the playoffs panting, the team’s core had to find some room in the regular season to rest and Nellie’s mix of lighter loads in practice and in performance appeared the appropriate tonic.

No longer would Derek Harper have to build possessions up by routine, the point guard could instead stand behind the shortened three-point line in anticipation of the long shots that Nelson liked risking his reputation on.

John Starks, meanwhile, could come off the bench behind a low-possession floor-spacer like Hubert Davis — a lengthy 6-5 and 46 percent from behind the shortened three-point arc as a Knick.

Starks would turn his twirl against second-tier talent off the bench, dominating the ball as his talents demanded. John won the Sixth Man of the Year Award in 1996-97 as a Knick behind Allan Houston, efficiently effectuating the dream that Nelson had for him.

The ability to articulate that sense of stargazing, the assertion that turns the audience into adherents, that’s what separates the stories. Athletes get to go out most every night and express themselves, to have their say, the great coaches are the ones that somehow stand tolerating all that.

Nellie never let the New Yorkers act themselves, his rigid characterization of each prevailing members of the Knicks got in the way of what basketball could have eventually given everyone. The Knicks reached out to Nelson with the idea that his service as coach (and coach only) would return Nellie to whatever blend of altruism drove him to become a leader in the first place.

He failed himself and New York in that sense, but Nelson is only one of dozens to do that with the Knicks. Grinning, luxuriously, until the building that nobody’s ever owned pockets another large number.

ROCK STEADY

(This recording features Richard Tee on keys, Chuck Rainey with bass guitar, Bernard Purdie on drums, with Cornell Dupree from Ft. Worth, TX on guitar. Donny Hathaway and Robert “Pops” Popwell are also on board.)(More to come.)