When Dallas earned its blue

Dallas worked its final game of the 1987-88 season on June 4th, in Game 7 of the 1988 Western Conference finals.

The defending champion Los Angeles Lakers banded to down the visiting Mavericks 117-102, knocking Dallas back to nil in the fledgling franchise’s quest for an NBA championship.

Each team really only worked seven players in Game 7, neither side could take any chances.

Mavs coach John McLeod didn’t even shake things up once the loss finally hit garbage time, once the Lakers finally put the Mavericks away, his starters remained on the floor.

McLeod fielded two reserves all afternoon: Brad Davis for seven minutes, Roy Tarpley for 32.

The 53-win Mavs hadn’t come nearly this close to a championship in the franchise’s eight-year history but Los Angeles was primed. The Lakers ran nervous as hell over twin centers, bad bounces, and all the other rotten luck that knocked L.A. out of the Western finals two years prior.

Los Angeles had seen enough up-and-comers, 1986’s stinging loss to Houston only gained in ignominy with the Lakers’ dominant run toward the 1987 championship.

Pat Riley ticked off the title defense by guaranteeing consecutive Laker rings during his team’s victory parade, the NBA hadn’t enjoyed back-to-back winners in 19 years by 1987-88 and that season’s Lakers (who struggled in a seven-game semifinal series against Utah) weren’t exactly assured of a streak.

The Dallas Mavericks were not exotic to the Lakers, Dallas lost to Los Angeles in the second round in 1984 and 1986 and Utah’s second round seven-game snort gave the champs severe pause.

Though the Mavs barged through Houston and Denver in the first and second rounds, Riley’s crew diligently pounded the visiting Mavericks by a combined 37 points in the first two contests of the Western finals.

Mavs’ team owner Donald Carter thought an 0-2 deficit as good a spot as any to reach out to Roy Tarpley, Dallas’ second-year reserve center.

“Have raw meat for lunch,” Carter directed the 23-year old on the day of Game 3.

“But don’t get so much you don’t want any more tonight.”

Tarpley enjoyed 20 rebounds and 21 points in Game 3, a Mavericks win, he contributed another double-double (with five blocks) in Game 4 as Dallas tied its series.

Los Angeles returned to its blowout form at the Forum in Game 5 before CBS’s Thursday night lineup broadcast the Mavs securing a squeaker at Reunion Arena via Game 6.

Los Angeles earned its chance at its repeat with a win in Game 7, the Lakers finally out-rebounded Dallas while shooting 55 percent from the floor. L.A. missed only one free throw in 22 attempts.

Mavs forward Mark Aguirre averaged nearly 25 points per game in the series against longtime rival Magic Johnson, yet all anyone could talk about was Tarpley.

Days after winning the NBA’s Sixth Man Award, Tarpley dominated Los Angeles’ championship front line on the way toward averages of 16 points, 13 rebounds and two blocks per game. He totaled 10 steals in the series.

“He’s a demon,” Michael Cooper pointed out.

Well, yeah, there’s always some of that.

Tarpley was already known.

The Mavs were well cognizant of the hard-charging reputation that dogged Tarpley at Michigan, where he led the Wolverines to an NIT title. It was the reason the 7-footer slipped to Dallas seventh in the 1986 NBA draft.

Dallas worked with found money during that process, years ago swiping a lottery pick from Cleveland for its 44-win team, the Mavs didn’t mind rolling the dice on a prospect that came with chatter.

Tarpley entered a rehabilitation clinic soon after 1986-87’s so-so rookie campaign — cocaine and alcohol. By the time he’d taken his second tour of the States in 1987-88, the center was already a major player in the NBA’s ongoing rehab reel of “I’m better, now”-features:

“I came very close to the edge,” Tarpley explained to the Chicago Tribune’s Sam Smith a month before the 1988 playoffs.

“Every night now I thank God for letting me get through one more day sober. It feels good now to wake up without a hangover.”

Roy was rolling by now, peeling off Dallas’ bench for first-year Mavericks coach John McLeod, yanking rebounds at the league’s highest rate in 1987-88.

“I’ve never had a player as dominant in one phase of the game as Roy,” McLeod told the Tribune.

“He can be like a [James] Worthy that rebounds better,” gushed Mavs assistant Clifford Ray, a former 10-year NBA pro charged with tutoring Tarpley.

After her son’s first rehabilitation stint, Tarpley’s mother left her job as a bank vice president in New York to move closer to Roy in Dallas, leaving behind 21 years at the same company. By the start of the series with Los Angeles Tarpley was approaching one year of sobriety, the NBA tested him daily.

During the same postseason a leak informed the Dallas press that Tarpley had stopped attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, so the 25-year old made a point to duck into a Los Angeles-area meeting during the Laker series.

Far less encouraging was Tarpley’s weariness in the face of the demands of what had become a sort of professional sobriety.

“I’m tired of talking about it. What upsets me is that I’m doing so well, and that's all people want to talk about. It (drug abuse) is a mistake that a lot of people have made.”

Tarpley fell victim to his illness early in 1988-89 while languishing on the Mavericks’ injured reserve with a knee injury. The NBA suspended Roy indefinitely five days into 1989 for his second strike.

“People close to Tarpley told the Dallas Morning News” that his suspension was coke-related.

A few days after he left the team to enter a clinic, a Dallas-area drug dealer pegged himself as a supplier familiar to Tarpley.

The 1988-89 Mavs were 17-12 at the time of the report, losers of three straight, three games behind the Western-leading Los Angeles Lakers.

Mavericks teammates were hardly sympathetic. Even Dallas can get cold in the winter.

“[He] could dominate a game when he wanted to, only when he was in the right frame of mind,” Rolando Blackman explained.

“You just can’t let your teammates down, and he let us down a lot.”

Mavs starting center James Donaldson made his first All-Star team in 1988, he was keen for a Maverick rebirth midway through 1988-89.

“I’m ready for somebody to come in here who’s willing to play hard every night,” Donaldson chipped.

“Sometimes [he] would just loaf.”

Center/forward Sam Perkins was perhaps Dallas’ least reverent:

“Today should be an all-day party because he’s gone.”

Each of these particular remarks weren’t crafted to sting Roy Tarpley, rather longtime Maverick Mark Aguirre — Dallas’ leading scorer and easily its least-loved Maverick.

The Mavs respectfully clammed up when Tarpley left for rehab in January yet went on record with abandon once the frustrated Aguirre was excised from the locker room in Feb. 1989, traded to Detroit.

The Mavs received small forward scorer Adrian Dantley in return, which made Dallas reserve Detlef Schrempf available at the same trade deadline.

Lacking playable interior muscle in Tarpley’s absence, the 26-year old Schrempf (who didn’t make it off the bench in Dallas’ Game 7 loss to Los Angeles) was shipped with a second-round pick to Indiana for 31-year old pivotman Herb Williams. The pick Dallas conveyed to Indiana was later used on center Antonio Davis.

Dallas was desperate, the three-game losing streak that met Roy Tarpley’s suspension had chafed into a 4-11 January.

“Mark’s attitude made it difficult for the team,” John MacLeod pinned. “It was a big problem.”

Aguirre’s unwieldy 11-year, $11.1 million contract was set to run through 1997, a bummer for both sides as the three-time All-Star and 21.7-point scorer’s contract ranked well, well out of the NBA’s highest order.

The 29-year old Aguirre (at $715,700) made around half as much as Warrior Joe Barry Carroll, the NBA’s 15th-highest paid player in 1988-89. The Maverick operation — a sellout basketball team in a booming, yuppie town — ran a little skinflint.

The Mavs’ $5.6 million payroll was the NBA’s third-lowest (Utah, Washington) among non-expansion teams, half as much as the Lakers’ total payroll. Aguirre rival Magic Johnson also signed a shortsighted contract earlier in his career — 25 years for $25 million — before the Lakers renegotiated terms (following a Johnson complaint).

Dallas didn’t see any reason to do that for Mark Aguirre.

And the guy Aguirre was dealt for didn’t see any reason to do anything for Dallas.

“We respect Adrian Dantley and respect his desire to be left alone for a few days and come here as soon as it is practical,” said Mavericks general manager Norm Sonju.

“We'd love for him to be here tomorrow. But that's not going to happen.”

When reporters asked Dinitri Dantley if her husband was hurt by the deal to Dallas, she ran to the point.

“Sure he is. Wouldn’t you be?”

Rumors swirled regarding Isiah Thomas’ leverage in pushing Dantley out of his locker room, conveniently returning Thomas’ friend Mark Aguirre.

Pistons coach Chuck Daly wanted the deal, in large (and profane) part to free minutes for the emerging Dennis Rodman, a starter.

Adrian was more concerned with his future on the 26-21 Mavericks.

“I can’t talk right now, but I will later,” Dantley told Detroit reporters. “I told you (the trade) was just going to be a matter of time. It has nothing to do with basketball.”

Asked if the trade involved a personality conflict, Dantley said: “It’s a management decision. Players do not have any input.”

Dantley eventually reported to the Mavericks, Dallas went 11-20 with his 20.3 points per game in the lineup, finishing the season with a 38-44 mark.

A year after pushing the Lakers toward the brink, the Mavs missed the playoffs.

At least they’d get a lottery pick.

Sports Illustrated was not shy in its expectations for Louisiana Tech forward Randy White.

In a beaming profile prior to the 1989 NBA draft, the magazine outlined several reasons as to why the 21-year old was set for NBA life as Karl Malone’s second coming.

Randy White averaged 21.5 points and 10.3 rebounds in his junior season, he made 17-38 three-pointers (47.7 percent) in 32 games during the 1988-89 season. The 6-8 power forward was from Keithville, La., a small town not dissimilar to Malone’s hometown of Summerfield, Louisiana.

Randy trained with Malone in summers between stints at school.

“He’d call me lazy,” White told Sports Illustrated.

The Mavericks passed over Karl Malone in the NBA draft five years prior in exchange for Detlef Schrempf, the team was determined not to make the same mistake again with a lottery pick earned from its mess of a 1988-89 season.

Dallas selected White eighth overall in 1989.

Any one of the nine guys taken after White — even Todd Lichti — would have served a superior choice.

Randy White is not mentioned on Keithville, La.’s Wikipedia page.

The Mavericks appeared a model franchise from its outset, handling rookie Kiki VanDeWeghe’s initial NBA holdout with ease while raiding the Cleveland Cavaliers for additional draft picks — selections used on fixtures Derek Harper, Sam Perkins, and Roy Tarpley.

In 1988, a few weeks after yanking the by-now back-to-back champion Lakers to a Game 7, the Mavericks dealt its first-round draft pick to the expansion Miami Heat on the condition that Miami select the rights to Dallas 1980 expansion draft choice Arvid Kramer top overall in the 1988 expansion draft.

Miami agreed not to pluck Mavs prospects Mavs prospects Bill Wennington, Uwe Blab, or Steve Alford from the group’s roster.

None of these Maverick twentysomethings appeared in Los Angeles during Game 7 yet each appeared heartier to Dallas than some of the selections that hit below the No. 20 pick the Mavs sent to Miami: Jerome Lang, Randolph Keys, Mark Bryant, David Rivers, Brian Shaw.

Miami chose combo guard Kevin Edwards, who’d average double-figure points in his first eight seasons. Wennington, Alford and Blab failed to develop in 1988-89, encouraging Dallas’s deal to move Detlef Schrempf for Herb Williams.

Additional depth was also dealt a blow in 1986 when the Mavericks drafted Mark Price in 1986 prior to quickly trading the future All-Star to Cleveland, 1987’s draft saw Dallas selecting Jim Farmer a spot ahead of Reggie Lewis.

Dallas remained under the salary cap and extended its own free agents in 1989, even Roy Tarpley, who received a three-year extension on a deal that now lasted through 1993-94.

He’d begin 1989-90 as a starter, opening the season with a 23-point, 17-rebound, three-block and two-steal effort in a loss to the Lakers. Five games later, Tarpley delivered 26 points and 22 rebounds in an overtime victory in Seattle.

The following evening Tarpley was pulled over by Dallas police for tailgating another vehicle at 70 miles per hour.

Tarpley was charged with driving under the influence and resisting arrest, he was suspended without pay. The Mavericks were 2-4 at the time, coach John McLeod would remain at the position for another week before giving way to beloved assistant Richie Adubato.

Adubato led the aging team back to the playoffs in 1989-90, with Tarpley returning for the season’s final half plus the postseason (a three-game sweep at the hands of Portland).

“We made the deals we made last year thinking we would have the chemistry we needed this year. There wasn’t a person in this organization who didn't feel we were going to try to win it all this year.” — Donald Carter.

In its 1990 offseason, Dallas traded two first-round draft picks for Lafayette “Fat” Lever, a 30-year old coming off an All-Star campaign.

Carter’s Mavs began 1990-91 with wins in three of four games, Tarpley averaged 24 points, 12.2 rebounds and 2.2 blocks per outing. Before the fourth contest, a win over Orlando, the Mavs were told Fat Lever would need surgery after a knee setback.

Later in the evening, during the first quarter, Roy Tarpley tore his left ACL. The Mavs announced that both Lever and Tarpley would be out for the remainder of the season.

Tarpley picked up two more DWI charges before the 1990-91 season completed, resulting in an indefinite suspension.

When Tarpley refused a drug test the next autumn, his third strike, the NBA banned him for life.

“The organization kept putting their eggs in certain players, and those eggs cracked.” — Sam Perkins.

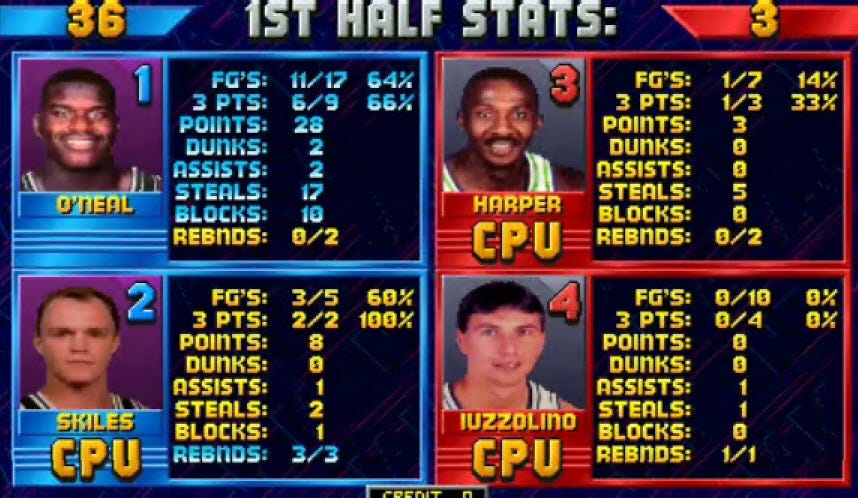

The Mavs, behind Mike Iuzzolino, pressed on without Tarpley.

“The problem with Roy,” Richie Adubato explained in 1992, “is that he’s such a super talent that as soon as he stepped on the floor you won every game. It’s hard to turn your back on that type of talent.”

It was before Christmas, the 1992-93 Mavs were off to a 2-19 start, Roy Tarpley was at least two years away from his first chance at applying for NBA reinstatement.

Ohio State scoring stud Jim Jackson, Dallas’ 1992 draft pick, was deep into what would become the NBA’s last rookie contract holdout. Jackson threatened to re-enter next June’s draft simply to avoid Dallas.

Adubato was thinking ahead.

“If Jackson could be developed here, and you got [Donald] Hodge and you got [Sean] Rooks and you got [1991 lottery selection Doug] Smith and you got Iuzzolino and you got a lot of young guys and you're going to get a high draft pick next year, and then Roy Tarpley walks in the gym.

“It’s like, look at San Antonio at 21-61 (in 1988-89). David Robinson walked in and they won 50.

“Roy Tarpley walks back in here next year, we win 50 games. I don’t care who we have, because Roy Tarpley is better than David Robinson when he first came out.”

STARTING AGAIN

(Gorgeous piece of Yacht for your Wednesday.)

Thank you for reading!

This is the stuff we do all summer. Long deep-dives meant for you to relax to, clicks and links meant for wasting time and encouraged context.

I try not to bash any heads with the point, basketball does that for us.

We have a lot of fun, and your contribution (really come on what is five bucks) goes toward more and more of these explorations. That’s what basketball does to us.

(More to come.)