Every Steely Dan Song: This All Too Mobile Home

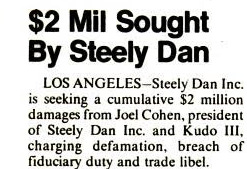

When the Touring Dan last convened in Glendale’s spring Porcaro was still 19, yet his on-air credits with Sonny and Cher were about to land him $400 a week to hit the road with the band. Becker and Fagen’s hopes for a structure reminding of the “European-styled social democracy [they] so admired” had taken a hit – nobody else in the group was making more than $250 a week on these dates.

Becker and Fagen’s self-examined “neocolonial devil’s bargain” frayed further with the presence of Jim Hodder, the band’s original drummer, who still stood in frame for the band’s last inner sleeve.

Hodder’s resolute stickwork hadn’t yet been told to hit the bricks by the time of the 1974 tours, and even Porcaro’s status wasn’t fully assured – that’s session legend Jim Gordon playing the drums on ‘Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,’ the first tune on the new ‘Pretzel Logic’ LP, the group’s latest single.

Sensing a groove worth embracing and a confrontation worth avoiding, Becker and Fagen decided to field Porcaro and Hodder at dueling drum sets for the ‘74 tours because, I don’t know, the Mothers did it.

(if the YouTube skip doesn’t work, trip ahead to the 1:06:55 mark.)Or, probably, because some iteration of Duke Ellington’s band did it. And the Allman Brothers. And whatever Donald and Walter talked themselves into because, shit, nobody really needs to know what’s gonna happen on the next album and, man, those two really sound good together.

Jimmy Hodder wouldn’t play on another Steely Dan LP after this tour but he sure as hell played his way off the stage. Porcaro leads like he’s on leave and Hodder, through his drive and swing, reminds of why Donald and Walter wanted him around in the first place. Put-upon Hesse’ian aggression, for them to snort at and appreciate.

Steely Dan’s initial aversion to touring was legend among red-headed DJs, the group was the Next Decade’s half-answer to what Memphis and Manila did to the Beatles until Don and Walter strapped on the two sets in time for the 1993 reunion tour.

The group’s original band, by comparison, was forced into a haphazard string of dates worked sometimes in support for bands that sounded nothing like Steely Dan, as if any group ever did.

Tours shoddily assembled by a record company that months earlier had no idea they’d had a band on their hands, let alone one with hits, the group was sprung far and wide to blank and blanker touring destinations that seemed interesting in name only – the Dan had to travel an entire week just to get a line that sounded good next to “Santa Fe.”

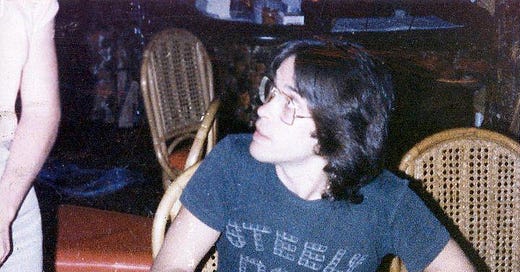

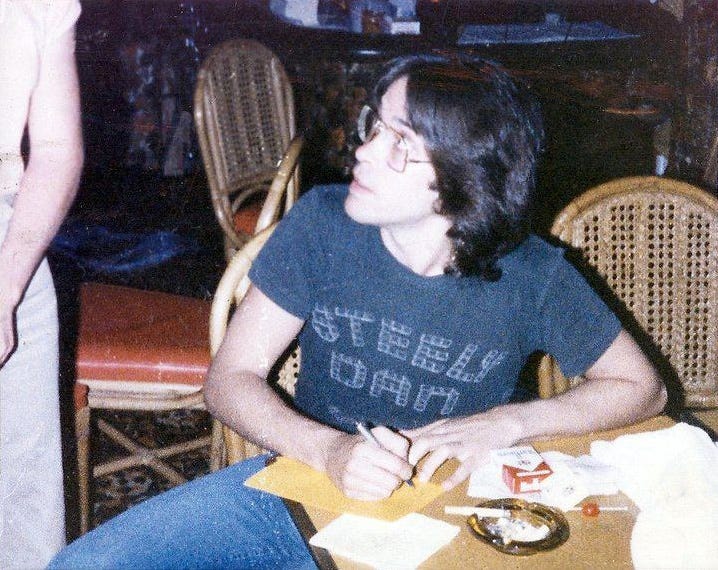

The younger of the songwriting duo, Walter’s onstage role by the 1974 tour was to hideaway under a pair of headphones next to all manner of active and inactive electronics and Jeff Porcaro’s hi-hat, cracking jokes in the free moments between the din. Porcaro was closer in age to Becker than anyone else in the original Steely outfit.

Walter was a thunderbird back there, adding an updated sense of terror to the original lines while insisting the outfit never lose its swing. Even in hiding, the power came from rear wheels.

By the time London hit, Skunk Baxter had acquired a Les Paul guitar and, while his licks didn’t weigh anything down, the optics weren’t good. Allowed to let loose on what seemed like a stomper on ‘Mobile Home,’ Baxter instead picked his spots on a song that may or may not have been able to be played on an electric guitar.

Fagen sings as if he doesn’t have to do this again, until the next night at least, same as the man filling the tank.

You can hear a bit of real life hopelessness in this song, strange for Steely Dan, inert as Arizona turns into New Mexico, or maybe the other way around. Bad or no weed, no or bad soundchecks, futility projected all over whatever dip is stuck behind the wheel.

"All our lyrics are calculated and literary," says Becker. "They are not personal documents. We use autobiographical material, but the autobiography is not what the lyrics are about."

They’d never record the song, at least to their liking, the opening piano lilt later partially found some of its way into ‘Sign in Stranger.’

Steely Dan only performed it once after the reunion, at a show in New York back in 2011. What’s left, with too much gone, is this document:

Players peeled off the stage until only the drummers were left. Michael McDonald gamely kept with those Becker and Fagen chords on that Fender Rhodes, leaving the view just after Baxter and Denny Dias (furiously scribbling chords) unburdened themselves.

With all that lost, bassist Becker has room to thrust into some sort of Forward Jazz Solo, partner Fagen knows exactly what to do and the result is what you’d expect in 1974 had Bard seen fit to let them stay without interruption. Donald throws in a blues sample, they finish each other’s sentences.

Then you get a drum solo, because the Mothers and the Brothers. Donald says “sweet dreams, my brothers, goodnight” because this is London and it’s 1974 and, hey, the guy can read a room.

Jeff Porcaro leads the solo, in a way, while Hodder bashes accompaniment alongside the kid’s goading – nobody’s trying to take anyone’s gig, here.

This is before Jeff learned to shuffle in a way that he didn’t feel was corny, before he’d been sent home from the studio by Fagen to stick up on Dannie Richmond while Walter was (just as importantly) off pricing new and obscene examples of outboard invention. Porcaro would spend the whole of ‘Katy Lied’ telling anyone that would listen that they had the wrong drummer for the job, and sometimes Don and Walter listened: Hal Blaine on Line One.

Porcaro would make every attempt to stay in his lane, but, he’s Jeff Porcaro. Why wouldn’t he burn like this in 1974, his Year 20 season? It’s human nature.

(After the song hit the dozen-minute mark a member of the touring outfit, perhaps Jeffrey Baxter, runs out to yell “OK, LET’S GO … dude … dude? … DUDE,” signaling the end of the show and also the close of the drum solo.

Every tune from the 1970s should have ended like that.)

It had to question itself and what it was doing with all that it had learned and Cashbox’s hold on all of it. All these guys can play, now, but that doesn’t mean there were more cars in the caravan, it just meant there were more people in the car.

And that car had to get off the road, and back into a studio.